In case the title didn’t tip you off, this post contains pictures of a lamb brain and details on its preparation for human consumption. If that bothers you, there’ll be a new post tomorrow that you’ll like better.

“Because of their delicacy and easy digestibility, spine marrow and brains are of great nutritional value for children and old people.”

-Escoffier, La Guide Culinaire

I would say that I eat more offal than most. I don’t really seek it out, but by buying whole animals, there’s always some available to me. Most of the offal I eat is from lambs, which is weird, because most of the meat I eat is from pigs, cows, and chickens. The main reason that I have so much lamb offal is that every year I make haggis for Burns night. That has me buying enough lamb lung, heart, and liver to feed anywhere from ten to forty people, depending on the year.

The reason I can do this is because Vicky and Shayne Horn at Tangle Ridge are so amenable. I remember the first time I made haggis, walking from booth to booth at the Strathcona market asking for sheep’s lung and stomach, and being treated like a freak by a couple of producers. The first year I bought a lamb from Tangle Ridge, I asked in passing if there was any offal available. They basically said you can have as much of whatever you want, and they went out of their way to get it for me.

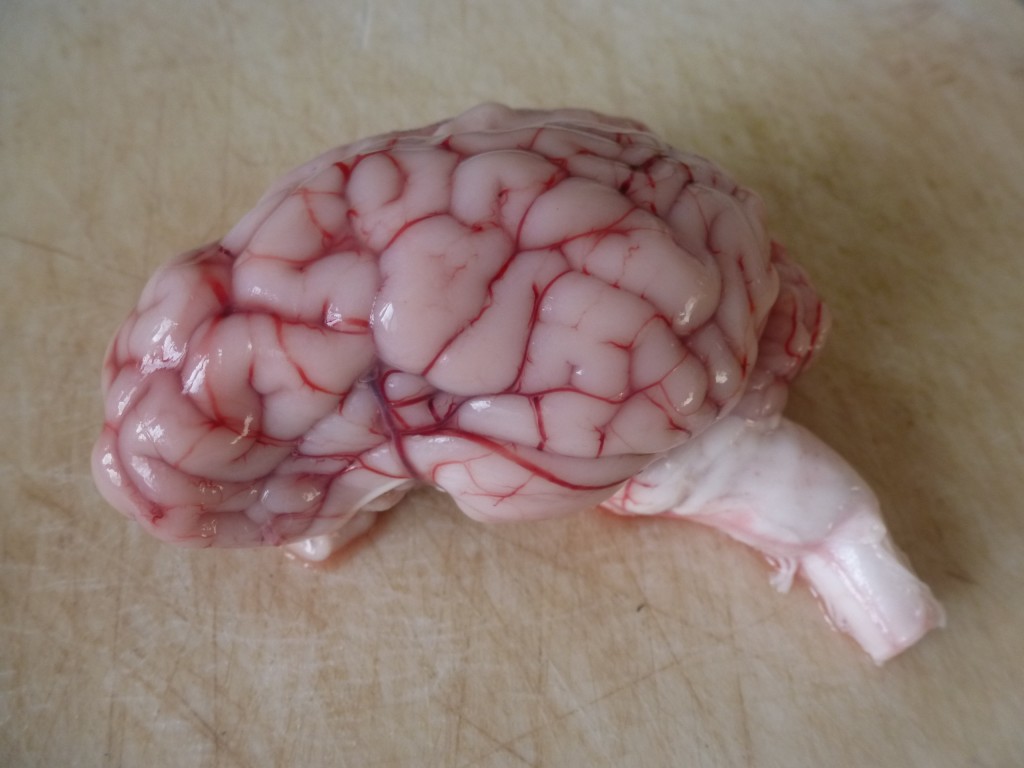

This year, besides the usual haggis requirements, I got a lamb head from the Horns. Since lambs aren’t split down the spine like pigs and cows, the head is in tact. This means you have the brain of the animal.

I’d never eaten brains before this fall. Honestly I had some reservations, mostly due to some comments in the most recent issue of Lucky Peach,[1] but then I figured: Thomas Keller serves calf brain, and Fergus Henderson devotes an entire chapter of The Whole Beast to lamb brain, so I probably shouldn’t worry too much about it.

The most difficult part of the operation was removing the brain from the skull in one piece. You can remove the jaw by cutting away the cheeks, opening the mouth, cutting away more connections, prying the mouth further, and so on. To open up the skull I used a cleaver and a mallet. Start by tapping the cleaver through the skull at the forehead. Be careful not to go too deep or you’ll damage the brain. Then use the mallet to drive the cleaver around the circumference of the skull. Eventually you will be able to pull the skull apart and remove the brain.

The brain itself is much more delicate and squishy than I anticipated. I though it might feel like plastic, or clay. It’s closer to a sack of viscous fluid. If you took high school biology, you’ll roll your eyes at the following (I didn’t, so it was new and fascinating information to me): besides the familiar left and right hemispheres, there is a third part of the brain, in the middle, at the back, called the cerebellum. It connects to the brainstem. You have to handle the brain very delicately or it will break along one of these three divisions.

As a first go-around, I simmered the little brain in vegetable broth. The only true recipe I have for lamb brain is in Henderson’s The Whole Beast, but in his characteristic, understated style, the only guidance for cooking is, “poach gently for eight minutes,” giving no indication of desired doneness. In my brief experience, I can tell you that I don’t think eight minutes is nearly long enough. Perhaps my lamb brain was larger than his, but I doubt it, because my lamb was only 35 lbs (are Canadian lambs smarter than British ones?) I poached my lamb brain for ten minutes, and it was still quite pink in the middle, so I returned the wobbly lump to the pot for another two minutes. It finished with a blush of pink in the middle, a “medium well,” if you will. I hope that’s okay, because then I ate it.

I let the brain cool to room temperature, then separated it into lobes, and sliced it to expose the beautiful, cauliflower cross-section. The “stem” of the cauliflower print was the white matter of the brain, the “florets” were a pale grey. Even cooked, the brain tissue had a creamy, yielding texture. I shingled the slices on buttered toast, seasoned with fleur de sel and black pepper, and finished with some oregano leaves.

I would describe the flavour of brain as muted liver. The texture was frankly incredibly: silky and smooth, like eating custard.

1. The comments are in the article, “American Cuisine: Whatever That Is”. Jonathan Gold says he avoids brains for three reasons:

Firstly, cholesterol exists to be your brain. There’s nothing in a brain that isn’t cholesterol. So you’re eating pure cholesterol, which is something to consider.

Second, the shape of brains is so convoluted that bacteria can hide anywhere in there, and there’s nothing that you can do about it. It’s not like muscle meat, where the interior tissue is sterile.

The third thing is that there are all those brain-related diseases like scrape and mad cow, and they’re completely impervious to heat.