When I was little, to me there were two essential facts about my grandparents: they lived on a farm, and they fought in “the war,” that is, WWII. Even though they never spoke to me about the war, it was central to my understanding of who they were. Possibly it was more important to my understanding of them then it was to their own. I’m sure that Grandpa thought of himself as a husband, father, grandfather, deacon, and train-enthusiast before a soldier. Yet, there was a collection of old service photographs on top of the piano, unmoved, for decades. The shrine-like placement of the pictures told me that those years affected my grandparents profoundly, and that there was some sadness sleeping deep within them.

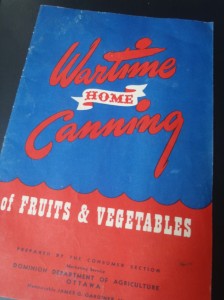

Growing up, I found that these two parts of my grandparents’ lives, the farm and the war, intertwined in the government programs aimed at reducing stress on resources through rationing, Victory gardens, and teaching people how to preserve food. I doubt that my grandparents bought into the imagery and language of the home front propaganda (“Your apron is your uniform!”) They had grown up on small farms during the depression, and were already well-seasoned in canning food and growing vegetables by the time the war came about. However, with brothers and friends fighting overseas, I suspect these activities took on a new significance.

Growing up, I found that these two parts of my grandparents’ lives, the farm and the war, intertwined in the government programs aimed at reducing stress on resources through rationing, Victory gardens, and teaching people how to preserve food. I doubt that my grandparents bought into the imagery and language of the home front propaganda (“Your apron is your uniform!”) They had grown up on small farms during the depression, and were already well-seasoned in canning food and growing vegetables by the time the war came about. However, with brothers and friends fighting overseas, I suspect these activities took on a new significance.

WWII periodicals on rationing, canning, gardening, and other forms of self-sufficiency resonate with contemporary talk of sustainable food supplies. Take the following excerpt from a 1942 BBC radio broadcast by George Orwell. They say there’s nothing new under the sun, and Orwell is clearly talking about “food miles,” though he doesn’t use that exact buzz-phrase.

If you have two hours to spare, and if you spend it in walking, swimming, skating, or playing football, according to the time of year, you have not used up any material or made any call on the nation’s labour power. On the other hand, if you use those two hours in sitting in front of the fire and eating chocolates, you are using up coal which has to be dug out of the ground and carried to you by road, and sugar and cocoa beans which have to be transported half across the world.

In other words, sensible, modest living and eating were important. Unfortunately, they require a kind of simple rationality that is almost extinct. Why, for instance, do we buy cranberries made of fruit harvested from Carolinian bogs, processed, canned, and shipped to our supermarkets, when cranberries grow along the North Saskatchewan?

The only kind of kitchen thriftiness that gets attention these days is eating obscure cuts of meat. My own ancestors weren’t particularly adventurous in that regard. They had their own reservations, and I’m sure that my grandma would find it strange that I now eat lamb’s quarters and buffalo. Their thriftiness was based more around things like saving pan oils, especially from bacon.

The pinnacle of my grandparents’ generations’ genius for kitchen economy was their use of left-overs. Of particular note is Aunt Dorie’s fried porridge. When there was porridge left over after breakfast, she poured it onto a tray and let it congeal. The next morning she cut the sheet of porridge into rectangles and fried them in reserved bacon fat. This is the kind of craftiness that I thought could only come from Italians peasants (think: polenta).

The pinnacle of my grandparents’ generations’ genius for kitchen economy was their use of left-overs. Of particular note is Aunt Dorie’s fried porridge. When there was porridge left over after breakfast, she poured it onto a tray and let it congeal. The next morning she cut the sheet of porridge into rectangles and fried them in reserved bacon fat. This is the kind of craftiness that I thought could only come from Italians peasants (think: polenta).

That wartime mentality would be a boon to Albertan kitchens. Despite what we see on restaurant menus and grocery store shelves, we live in a harsh province. Our food should be more humble and austere than that from, say, California.

We don’t need to be survivalists. In fact, complete self-sufficiency is a myth that has run wild in North America, especially on the prairies, with our “frontiersmen” heritage. That being said, we rely far too much on others to grow and cook our food.

Our backyards are Victory Gardens. Our kitchens are War Rooms.

Before the war there was every incentive for the general public to be wasteful, at least so far as their means allowed. We have learned now, however, that money is valueless in itself, and only goods count. In learning it we have had to simplify our lives and fall back more and more on the resources of our own minds instead of on synthetic pleasures manufactured for us in Hollywood or by the makers of silk stockings, alcohol and chocolates. And under the pressure of that necessity we are rediscovering the simple pleasures – reading, walking, gardening, swimming, dancing, singing – which we had half forgotten in the wasteful years before the war.

– George Orwell, from a BBC broadcast entitled Money and Guns, aired in January 1942