Spirits are distilled beverages, made by concentrating alcohol and other volatile, aromatic compounds to make heady, shelf-stable drinks.

Spirits are distilled beverages, made by concentrating alcohol and other volatile, aromatic compounds to make heady, shelf-stable drinks.

The sheer number of different types of spirits available in most liquor stores can be confusing. What, for instance, is the difference between Scotch whisky and Irish whiskey? Or tequila and mezcal? Why is all Cognac brandy, but not all brandy Cognac? These questions can be answered by knowing a few things about how liquor is made.

All spirits can be classified using the following four pieces of information:

- region of production;

- ingredients, including the base fermentable material and any other flavourings like spices or caramel;

- distillation details, including type of still used, number of distillations, and other nuances; and finally

- aging method, if any.

Region of production. Some spirits must be made within defined geographical boundaries to carry a certain name on the label. The most famous examples are Scotch (which must be from Scotland…) and Cognac and Armagnac (from the areas around the French towns of the same name). The argument for the protection of regional designations is that subtleties in the water, ingredients, even the air, give the product a distinct character. Regional designations are always accompanied by specifications on the ingredients and processes using in production. For instance, Cognac must be from the Cognac region, must be made from grapes, must be aged for a certain period of time, and so on.

Ingredients. All spirits begin as some sort of food that has sugar in it, whether fruit like grapes and apples, grains like barley and rye, or even sugar itself, in the form of cane juice or molasses. The first step in converting these foods to spirits is to turn them into a fermentable liquid. This is self-explanatory for grapes: you crush them to make juice, and there is in fact already yeast on the skins that will start to metabolize the natural sugars. The process is a bit more complicated for grains: generally you need to malt, kiln, grind, and mash them, just like when making beer.

Interestingly, the base fermentable is not always important in categorizing the spirit. Vodka, for instance, can be made from rye, or potatoes, or a number of other diverse ingredients. Some spirits are categorized not by the base fermentable, but by how it is flavoured. Gin can be made from any type of grain, but must be flavoured with juniper and other aromatics.

Regardless of the ingredients, yeast is added to the base fermentable liquid, and over the course of a week or two it metabolizes the sugars, creating ethanol as a byproduct.

After fermentation the mixture (now called wash) is relatively low in alcohol, somewhere around 5-15% alcohol by volume (ABV). ABV is determined by the quantity of fermentable sugar in the original liquid. There is, however, a ceiling on alcohol content with natural fermentation. Even if we were to pour a bag of sugar into our grape juice or barley mash, we could only ever get an ABV of at most 17%. Alcohol is a toxin, and fatal to yeast in such a high concentration. We must concentrate the alcohol and aromatics by distilling the liquid.

Details of Distillation. Distillation makes use of the different boiling points of the different components of a liquid. Water boils at 100°C at sea level, and ethanol at about 78°C. By heating a mixture of water and ethanol to a temperature between these two, then capturing and condensing the vapour, the distillate will have a much higher ethanol concentration than the original liquid. The ethanol, being easily evaporated, is called a volatile component. Often used to describe someone who flies off the handle, in the present context it means easily evaporated. Non-volatile compounds, including sugar and pigments, are left behind. All pure distillates are therefore dry (not sweet at all) and colourless.

What makes distilling challenging and interesting is that there are thousands of volatile components in fermented liquids besides ethanol. Some are more volatile than alcohol and boil off at lower temperatures. These are called heads, or foreshots, and are always undesirable in finished spirits. They include methanol, acetone, and are generally nasty and toxic. Other compounds are less volatile than ethanol, boiling off at higher temperatures. They tend to be long, fat-like hyrdrocarbon chains, and are called tails, or feints. They contribute harsh flavours that are desirable in small amounts in some styles of spirit, notably whisky. They also contribute to mouthfeel, producing the oily texture of some spirits. Tails are also known as fusel oils, and include butyl and amyl alcohol.

The art of the distiller is inviting the right volatiles to the party, while keeping out the undesirables. The guest list depends on the style of liquor they are making. Vodka, for instance, is a very neutral spirit, prized for it’s clean flavour. (One of the first Smirnoff ad campaigns in North America was: “No taste. No smell.”) Eau-de-vie and schnapps, on the other hand, are prized for their strong aromas of fresh fruit.

There are countless types of stills, but there are three important, classic styles used in commercial distilling.

Pot still. A large pot that holds the wash is heated. Vapours rise from the pot into a vertical pipe called a gooseneck, or swan neck. This pipe then narrows and bends towards the horizontal in a section called the lyne arm. Vapour then descends into a condenser.

The first liquid that dribbles out of the condenser contains the heads, which are discarded. Next the happy hearts are dispensed. Finally the tails, which may or may not be desirable in small quantities. The distiller evaluates the spirit to separate the heads, hearts, and tails depending on the style of spirit being made.

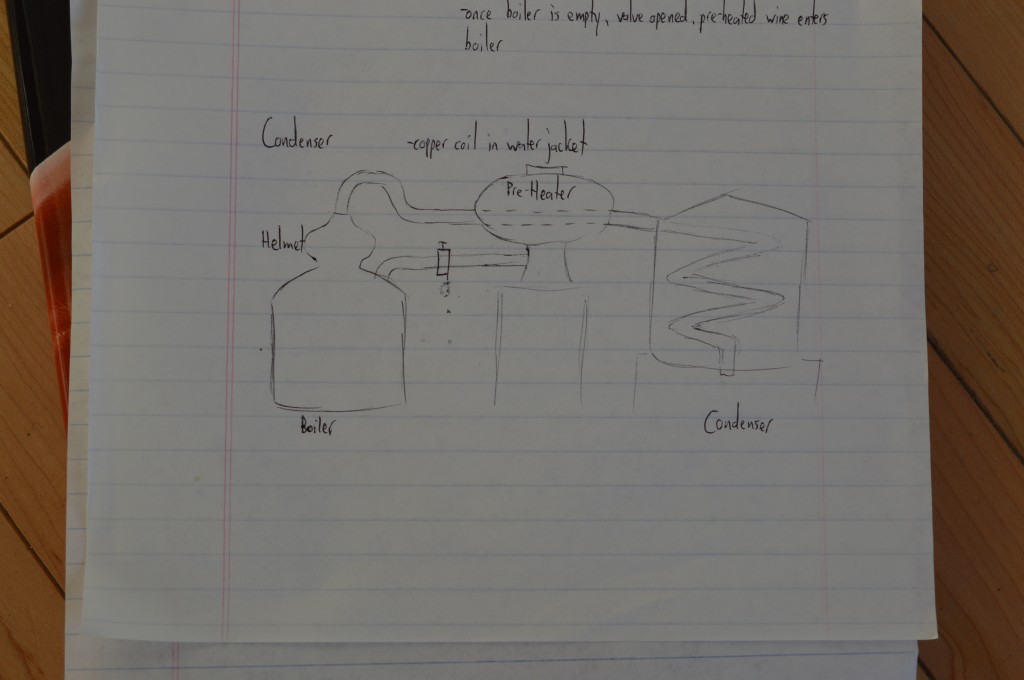

Charentais Alembic Still. Most associated with Continental, aromatic spirits based on fruit, such as brandy and eau-de-vie. Important features include the “helmet,” a bulbous top on the boiler functions as an expansion chamber, which holds back the heavier volatiles, and lets the lighter fruit aromatics through.

Usually the vapour passes by a pre-heater, containing the wash for the next batch.

Like a pot still, heads, hearts, and tails come out of the condenser one after the other, and have to be separated at the distiller’s discretion.

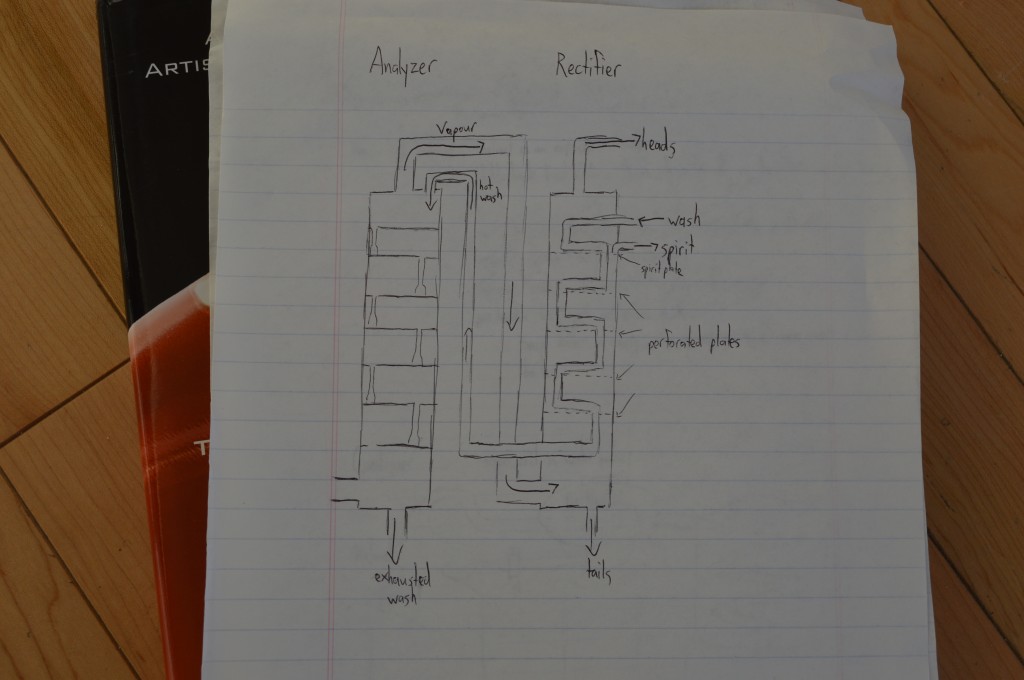

Continuous still. Most associated with industrial distillation of neutral spirits. As the name suggests, this still does not operate batch by batch, but with a continuous input of wash.

The cool wash descends and is heated by the rising vapour. Instead of heads-heart-tails differentiation being a function of time, as with batch stills, here it is a function of height. The more-volatile heads come out the top of the still, and the less-volatile tails out the bottom. The spirit is taken out somewhere partway up the still.

The number of passes through the still is also important. Scotch, for instance, is generally twice-distilled, while most Irish whiskey is thrice-distilled.

Aging method, if any. The most important question here: is the spirit aged in wooden barrels? All distillates are clear and colourless when they first come out of the still. The colour of brown spirits like whisky and brandy develops during barrel-aging. Besides changing the colour of the spirit, aging in wood makes the drink smoother, and can lend distinct aromas and flavours, notably the vanilla and caramel notes found in bourbon.

Based on the four points discussed above, we can now simply and accurately define every major style of spirit. A super-quick survey:

Whisky

- Region of Production: There are no controls on the term whisky, but its most famous sub-varieties are regional designation: Bourbon is from the US, Scotch from Scotland, Irish whiskey from Ireland, and Canadian whisky from Canada.

- Base Fermentable: Whisky is always made from grain, but the exact ingredients vary widely. Bourbon is based on corn, and Scotch on barley, for instance.

- Distillation Details: Traditionally made in a pot still that allows certain tails through.

- Aging Method: Always aged in wooden barrels to obtain characteristic colour, flavour, and mouthfeel.

- Contrary to popular thought, Canadian whisky is not necessarily rye whiskey, though it does generally contain a good does of rye. It pains me to admit, but Canada is the least regulated of the four classic whisky regions, and therefore the least distinct of the group.

Vodka

- Region of Production: There are no regional controls for vodka, but its homeland is Russia.

- Base fermentable: Any number of base fermentables can be used. Basically the cheapest source of calories available. Rye is the most common, but potatoes and wheat are also used.

- Distillation Details: Most commercial varieties are made in a column still, but pot stills can also be used. Often distilled several times for clean flavour.

- Aging: Not aged, or aged very briefly, but never in wooden barrels. Vodka is always clear.

Brandy

- Region of Production: “Brandy” itself can be made anywhere, but it is understandably most common in wine regions, and certain types of brandy are regional designations (Cognac, Armagnac).

- Base Fermentable: Grapes are fermented into a mediocre wine that is later distilled. The term “brandy” is also broadly applied to other distillates based on fruit. For instance, while the Normans have a word for apple cider distillate (“Calvados”, see below), but the English do not, so we often call it “apple brandy.” This is perfectly acceptable. Imagine if the English language did not have the word “cider,” and we had to call fermented apple juice “apple beer.”

- Distillation Details: Premium brandies like Cognac are made in Alembic Charentais stills.

- Aging Method: Always aged in wooden barrels to obtain characteristic colour, flavour, and mouthfeel.

Calvados

- Region of Production: Specific parts of Normandy and Brittany, in France.

- Base Fermentable: Apples, or sometimes pears.

- Distillation Details: Alembic still

- Aging Methodl: Always aged in wooden barrels to obtain characteristic colour, flavour, and mouthfeel.

Gin

- Region of Production: Not a controlled term, but originally from Holland and adopted with enthusiasm by the British.

- Ingredients: Usually a neutral grain spirit that has been flavoured with juniper and other exotic aromatics like grains of paradise.

- Aging Method: Almost never aged in wood. Almost always clear. (There are some exceptions by craft producers like Victoria Spirits.)

Rum

- Regional of Production: Not a controlled term, but originally from the Caribbean and other cane-growing regions.

- Base fermentable: Sugar cane juice, or molasses, or a blend of the two. Often caramelized sugar is back-added to the distillate for sweetness, colour, and body.

- Aging Method: Large commercial brands of rum are not usually aged. The best rums in the world (like this one) are always aged in wooden barrels.

Eau-de-Vie and Schnapps (true schnapps)

- Region of Production: Not a controlled term. Schnapps is common in German-speaking regions such as Germany and Austria. Most French regions, notably Alsace, use the term eau-de-vie. Switzerland can go either way. Etter is a self-described eau-de-vie, even though it is made in the largely German-speaking Swiss town of Zug.

- Base fermentable: Any manner of fruit, including apple, pear, apricot, plum, and cherry.

- Distillation Details: The best examples use an Alembic still to capture the aroma of the fresh fruit.

- Aging Method: Not aged in wood barrels. A clear spirit.

Mezcal

- Region of Production: Not a controlled term, but confined almost entirely to Mexico.

- Base Fermentable: Agave, specifically the swollen, central bulb of a mature agave plant that has had its flower stalk snipped. The bulb is cooked, then crushed and shredded to extract a sweet liquid.

- Distillation Details: Pot still, traditionally.

- Aging Method: Some mezcal is aged on wood, some is not. It is partly a stylistic decision. Cheap industrially-produced mezcal usually gets its colour from caramel, while very fine examples are aged in wood.

Tequila

- Tequila is a kind of mezcal produced in certain delimited areas of Mexico, using only blue agave.

- Tequila has different classifications based on aging method. Blanco is un-aged, or aged very briefly in stainless steel tanks. Gold tequila gets its colour from caramel. Reposado and añejo tequilas are aged in wooden barrels.

Grappa, Marc, and other Pomace Spirits

- Region of Production: Not a controlled term, but most common in wine-producing regions.

- Base fermentable: Grape pomace (the skins and seeds left-over after pressing grapes to make wine). Really cheap examples will use true pomace mixed with a bit of water and sugar. Really fine examples will actually use grape juice, but from later pressings.

- Distillation: Pot still, traditionally.

- Aging: Most often a clear spirit. The Cretain pomace spirit raki is often aged on wood. And there are some amazing Grappa di Barolo that are barrel-aged.

- In Greece the most common word for pomace spirit is tsipouro.

- Other notes: Grappa is often a little rough around the edges, but quality examples like Nonino Grappa showcase the natural aromas of the grapes from which it is made. Nonino Grappa di Moscato, for instance, has the distinct lemon balm aroma of the moscato grape.