Cooking an egg in its shell is proverbially simple. You drop the egg in hot water, set a timer, then remove the egg. That’s it. Commercial eggs are so uniform in size and shape that we can rely on the cooking times dictated by cookbooks. This is a very unique situation, as usually cooking times in cook books are completely useless. For instance, the time required to cook a piece of meat will vary wildly depending on the specific oven, stove, or grill being used.

Cooking an egg in its shell is proverbially simple. You drop the egg in hot water, set a timer, then remove the egg. That’s it. Commercial eggs are so uniform in size and shape that we can rely on the cooking times dictated by cookbooks. This is a very unique situation, as usually cooking times in cook books are completely useless. For instance, the time required to cook a piece of meat will vary wildly depending on the specific oven, stove, or grill being used.

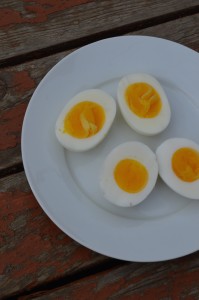

The ideal characteristics of a hard-cooked egg:

- Firm-but-tender white.

- A set yolk. The exact texture can be anywhere between soft and gel-like, and firm and granular, depending on the application.

- Some say that a centred yolk is important. I disagree.

- Smooth exterior after peeling. This is more important for some applications than others. Who cares what the exterior looks like if the eggs are destined to be chopped and put in a sandwich? Mostly we are concerned with the ease of peeling, which we’ll discuss below.

Cold-Start vs. Hot-Start. There are two methods for cooking eggs in their shells: cold-start and hot-start. For cold-start you put the eggs in a pot, cover with cold water, and fire up the stove. As soon as the water reaches a simmer, you reduce the heat to maintain that simmer, then set the timer. For hot-start you add the eggs directly to gently simmering water and set the timer. The alleged benefit of the cold-start method is that it is gentler on the eggs and reduces incidents of cracking. A quick online search shows that cold-start is the more popular method. I always use hot-start. It seems more precise to me. (When does a simmer really start? With the first bubble? With sustained bubbling? These are the philosophical questions raised by the cold-start method.)

Water Temperature. In recent years culinary-types have stopped referring to this method of egg cookery as “hard-boiling”, because the water is not really supposed to be boiling, but rather simmering gently. This is part of a broader linguistic movement that favours precise, literal words at the expense of traditional, colourful descriptors. Full-on boiling would jostle the eggs and increase the chances of cracking the shells. The higher heat might also over-cook the outermost white, making it rubbery and sulfurous. So yes, a gentle simmer is key.

If you screw up hard-cooking an egg, it will be because your water temperature wasn’t correct. As a fail safe you can use a thermometer to measure the water temperature before adding your eggs. It should be about 85°C.

Simmering Times for Hot-Start Method.

- soft-cooked: 6 minutes

- medium-cooked: 8 minutes

- hard-cooked, with gel-like yolk: 10 minutes

- hard-cooked, with pale, granular yolk: 15 minutes.

Most recipes suggest you remove the eggs to an ice bath to arrest cooking. Simple cold water works fine.

Peeling. Folks like to complain about how frustrating it is to peel hard-boiled eggs. If you use eggs are are a week or more old, the shells will slip off easily, leaving a perfectly smooth, glistening white.

Peeling. Folks like to complain about how frustrating it is to peel hard-boiled eggs. If you use eggs are are a week or more old, the shells will slip off easily, leaving a perfectly smooth, glistening white.

Don’t hard-boil fresh eggs. Or if you do, don’t whine about how hard they are to peel. It’s like grilling a beef shank and then complaining that it’s tough: if you had a beef shank, you should have stewed it.

What to do with hard eggs:

- Mostly you should just eat them.

- Chop or slice them and put them in salads. Potato salads, for instance.

- Chop them and make egg salad. I’m hard-pressed to think of a preparation that is further from vogue than egg salad. One day at Elm Café I made a dozen delicious egg salad sandwiches, spiked with raw red onion and celery and peppery mayonnaise, and we literally did not sell a single one.

- Make devilled eggs, which have experienced a very modest renaissance in recent years. Post forthcoming.

- Make pickled eggs. Post forthcoming.

- Make sauce gribiche. Post forthcoming.