This is something I’ve been meaning to write for a while: a series of posts on cutting pigs.

Like many Button Soup entries, the next few posts will be nit-picky, unnecessarily detailed, and lengthy. Oh: and graphic.

Regional Pork Cutting Traditions: American v. Austrian

There really is no wrong way to take apart a pig, so long as you end up with the cuts you want to cook or cure. There are, however, many traditional methods. References like Larousse describe the American, British, and French traditions, though there are countless others. In Canada we use a system almost identical to the American.

When I was cooking in Austria last summer, I came across some fantastic cuts of pork that I had never heard of. The Austrian method for cutting pigs is often called seam butchery because it tends to separate muscle groups along natural divisions and separate bones at their joints. The North American method is much more crude, and often divides the pig by cutting through muscle groups and sawing across bones. By way of example: when I butcher in the American style, I make seven or eight cuts with a hand saw; using the Austrian system I make one.

Generally speaking, the North American system uses the skeleton of the pig to landmark cuts. For instance, the hind leg is traditionally divided by cutting perpendicular to the leg bones at various points to produce a butt end (containing the hip bone), a centre cut (containing the femur bone), a shank end (containing the knee joint), and a hock (containing the shank bone). The Austrian system uses muscle groups as landmarks. From the hind leg they get cuts that we would call sirloin, inside round, outside round, tip, and hock.[1]

The Austrian pork chart is also much more detailed than the North American. Where we might see only one or two cuts, the Austrians often identify several. In North America we separate the pig’s shoulder into the blade and the picnic ham, whereas the Austrians convert the same piece of meat into a nape, thick shoulder, thin shoulder, and meat pocket.[2]

What I’m trying to say is that in studying the Austrian system you become much better acquainted with the characteristics of the different muscles, which will eventually make you not only a better butcher, but also a better cook.

I’m in no way an expert in pork butchery, let alone the Austrian style, but the particular way I cut up a pig is influenced by the Austrians.

This post discusses separating the pig into what are called primal cuts, or simply primals. We break the pig into a few large sections so we can work in modules.

The Side

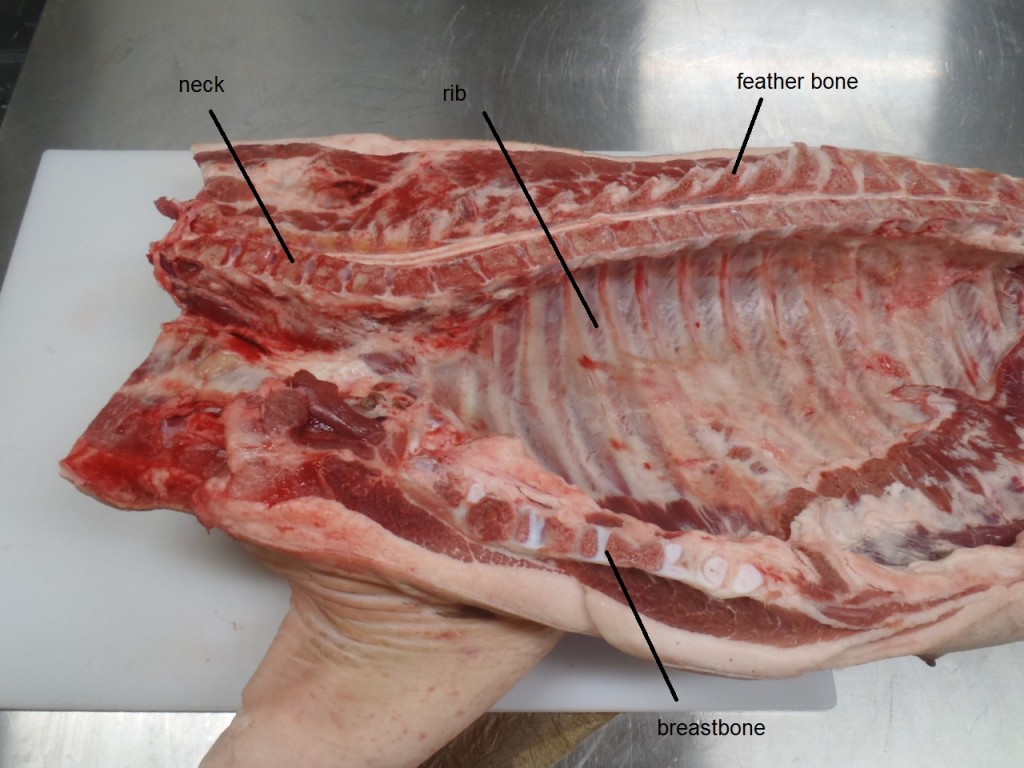

Below is a side of pork. It is one half of a pig. Pigs are eviscerated, then cut along the back bone in to two symmetrical halves at the abbatoir. We’re looking at the inside of the animal, obviously.

To the left is the head. Extending from the head you can see the neck bones. The neck bones, the bones between the skull and the ribs, are called cervical vertebrae. Looking to the right you can see the rib cage. The back bones that are connected to ribs are called thoracic vertebrae. The backbones between the rib cage and the pelvis are called lumbar vertebrae. Lumbar vertebrae don’t have any ribs coming from them, but they do have small bones, a few inches long, extending from them, parallel to the ribs. In butcherspeak these are called finger bones. In medicalspeak they are transverse processes. The vertebrae next to the pelvic bone are called sacral vertebrae. Finally are the tail bones, called caudal vertebrae. All vertebrae also have fin-like bones that stick straight up on the standing animal. Butchers call them feather bones. Doctors call them spinous processes. These feather bones are most pronounced on the thoracic vertebrae.

At the far right of the photo below is the hind leg. It is stretched out behind the pig because the animals are hung from their hind feet to chill after they are slaughtered and eviscerated. On the hind foot you can see “177” written in blue ink. This is the hook weight of the whole animal. This side of pork therefore weighs about 90 lbs.

Pigs are broken into four primals: shoulder, leg, loin, and belly. This side of pork also has the head attached, which is not technically part of any of the primals. We’ll start there.

Removing the Head

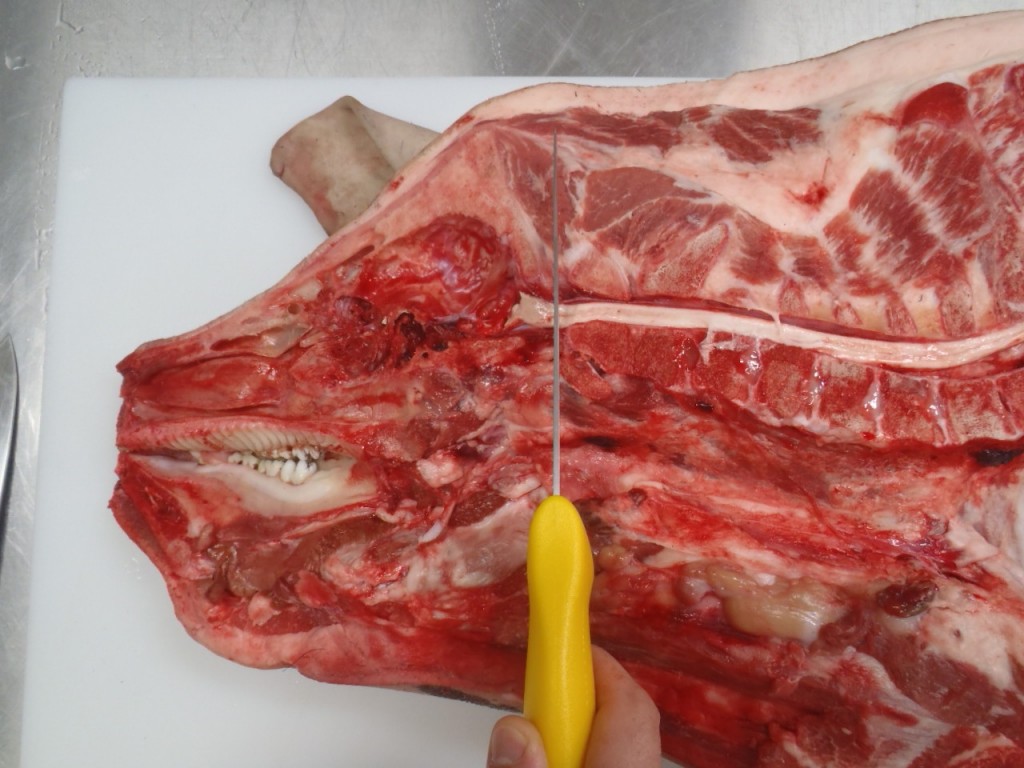

The cut to separate the head starts behind the upper portion of the skull. Cutting here will maximize the amount of meat left on the shoulder, and it should intersect with the atlas joint, which is where the skull meets the first neck bone. I cut through all the meat that I can, until the only connection between the head and shoulder is the atlas joint.

Once this cut is made, the head can be lifted to snap the atlas joint, like so:

At this point I give the head a turn around the broken joint, then cut the joint with a knife. Here’s what the side looks like without the head.

Leaf Lard, Kidney, and Tenderloin

In the lumbar region there is a big mass of fat. This is called leaf lard, and after fatback it is the most prized fat on the pig. It is analogous to the suet found in cows and sheep, and surrounds the kidney. The leaf lard and kidney can be pulled from the carcass in one piece without the use of a knife.

The leaf lard and kidney:

Beneath the leaf lard and kidney is the tenderloin. This is technically part of the loin primal but is often removed from the side at this point.

The majority of the tenderoin is tucked under the lumbar vertebrae. I cut under the backbones to pull the tenderloin away.

The head of the tenderloin is tucked into the hip bone. I follow the hip bone closely with my knife to maximize the amount of meat on the tenderloin.

This is the tenderloin straight from the side of pork. There is a fatty band containing glands that must be removed.

I used to spend time cleaning the remaining fat and silverskin off the tenderloin, but I’ve found that the cut is so lean and naturally tender that the meat actually benefits when these bits are left on.

Removing the Shoulder

Here’s the front end of the pig:

My aim is to separate the shoulder so that all the bones associated with the front leg (that is, the shoulder blade, the arm, and shank bone) are all left in the shoulder primal. By cutting between the fourth and fifth rib I ensure that the entire shoulder blade stays on the shoulder primal. Actually sometimes there is a cartiliginous tip from the blade bone that stays on the loin, but this is easily removed later.

Cut all the way through the flesh and skin. On young animals you can also cut through the breastbone with your knife.

Next I saw through the backbone, then cut through the rest of the meat with my knife. Shoulder primal: removed.

Removing the Leg

This is where the Austrian primals differ the most from the North American primals. In Canada, we typically separate the leg from the loin by sawing through the narrow centre of the hip bone. The portion of the hip left on the loin is then called the pin bone, and the portion left on the leg is called the haitch bone. The meat on the loin around the pin bone is called the sirloin.

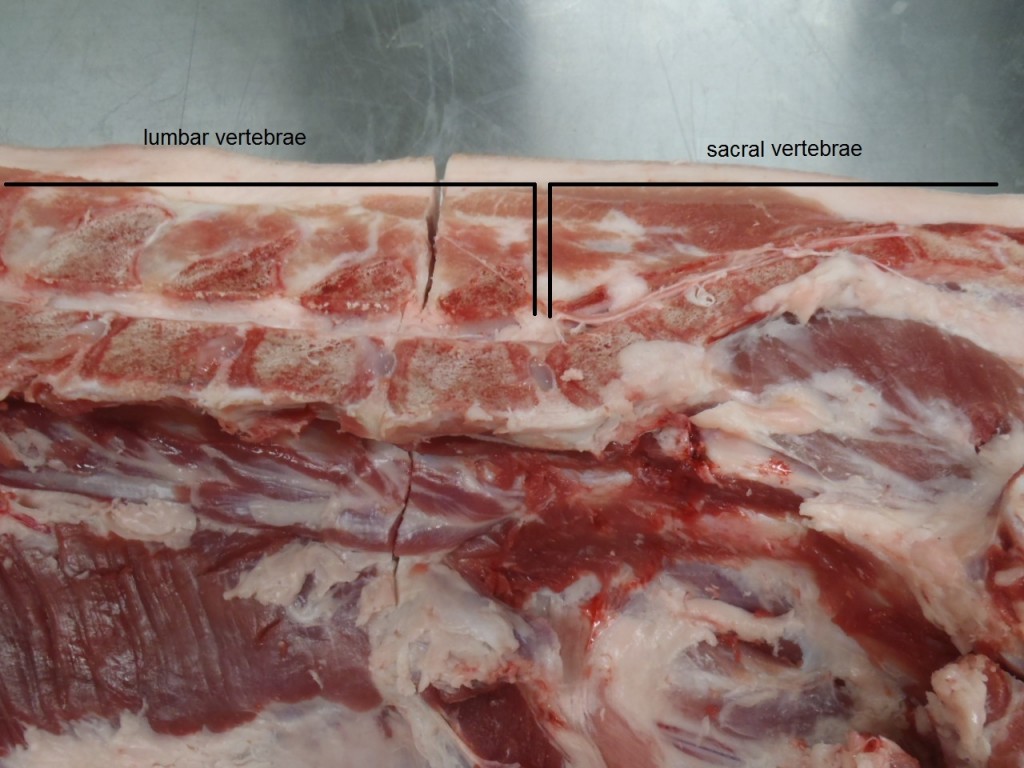

In Austria, the leg is removed from the side so that the entire hip bone and sirloin remain on the leg primal. The line of division is typically between the last and second last lumbar vertebrae. By cutting here we ensure that the entire hip bone remains on the leg primal. You can distinguish the lumbar vertebrae from the sacral vertebrae by finding the change in angle of the backbones. That first upturned backbone is the first sacral vertebra.

To separate the leg from the belly we locate a natural seam between the muscles.

Separating the Loin and Belly

This is what remains of our side of pork:

The line along which we separate the loin from the belly depends entirely on what we intend to do with the loin. I prefer bacon to chops, so I try to maximize the size of the belly. I therefore cut as close to the central, round muscles of the loin (sometimes called the “eye of the loin”) as I can. Let’s identify those muscles now.

This is the side of the loin that was once attached to the shoulder. It’s called the blade end of the loin, and on the top left you can see the round muscle group.

The side formerly connected to the leg is called the sirloin end.

I use my knife to mark the separation line along the ribs and cut through the meat of the lumbar section.

I saw through the ribs, then use my knife to cut through the meat beneath.

The side of pork is now broken into its primals. It has yielded us the following:

- head

- leaf lard

- kidney

- tenderloin

- shoulder primal

- leg primal

- loin primal

- belly primal

Now the real fun begins. Stay tuned.

1. Schlussbraten, Kaiserteil, Frikandeau, Nuß, and Stelze, respectively.

2. My translations of Schopf, dicke Schulter, dünne Schulter, and Fleischtasche.