When I first decided to make pemmican, I thought the process would be simple: make jerky, pound jerky, render fat, combine. In practice, there were a couple hiccups, but the results were surprising.

In the finest pemmican, the dried meat was pounded until it became a powder. I started grinding pieces of jerky with a mortar and pestle. It worked, but I realized it would take days to process a useful quantity of meat. I eventually found a rock and a solid piece of earth, wrapped the jerky in cloth and pounded it out. You could probably blitz the meat in a food processor and obtain similar results.

With my meat powder made, I ran into a problem:

Buffalo Fat

Buffalo fat is almost an oxymoron. The animal is very lean, and there is certainly nothing like the fatback on a pig. To complicate the matter, buffalo is dry-aged, a process that claims what little fat cap there is to protect the meat. It is therefore extremely hard to obtain raw buffalo fat in the quantity required for pemmican.

Buffalo fat is almost an oxymoron. The animal is very lean, and there is certainly nothing like the fatback on a pig. To complicate the matter, buffalo is dry-aged, a process that claims what little fat cap there is to protect the meat. It is therefore extremely hard to obtain raw buffalo fat in the quantity required for pemmican.

I had actually come across the solution to this problem ages ago, without realizing it. “The Plains Indians used to crack and boil bones to make grease.” It was right there in my notes, but I didn’t recognize “grease” as “edible fat.”

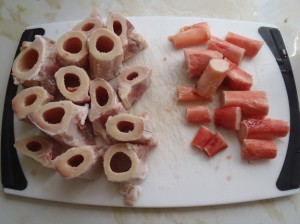

I had a bag of marrow bones (that is, leg bones cut into two or three inch lengths). To separate the marrow from the bones cleanly, I emptied the bag into a bucket of cold water. After a few hours of soaking I was able to push the cylinders of marrow out of the bones (photo above). Soaking bones in cold salted water, replacing the water as it clouds, is a common way to purge the marrow of blood. I don’t have a clear idea why the process makes the marrow slide out of the bones so easily, but it does.

These marrow cylinders can be rendered as if they were pure fat scraps: throw them into a pot with a touch of water and place over very low heat. I soaked my marrow extensively to draw out as much blood as I could, as I thought the blood might somehow taint the fat. I retrospect, I’m not sure this was necessary. After rendering for a few hours, I had beautiful fat with a layer of what looked like curdled blood on top. The blood that I was unable to purge had separated cleanly, and it didn’t seem to affect the fat in any way.

I strained out the non-fat components because a) they look gross, and b) they increase the rate of spoilage of the fat.

The next step was to combine the meat powder with the fat in roughly equal parts. Simple enough, though there is an important nuance: the fat must be just, just melted (ie. not too hot). If the fat is too hot, it will cook the meat powder and make it hard and gritty.

My reasons for making pemmican were quasi-academic, and truthfully I wasn’t expecting the dish to give a pleasurable eating experience. Of course the flavours of the jerky, smoke and juniper in my case, dominate. Salt is not traditional at all, as it wasn’t harvested by the Plains Indians, but by seasoning the meat and fat before cooling, this pemmican was actually damn tasty. The texture was strange, though not unpleasant. It was a bit like a rillette that you don’t have to chew.

This is a preparation that you could toy with. For instance: what if the jerky were simply pulled apart and mixed with the marrow fat, so that there was still a characteristic jerky chew? Dried saskatoons would definitely allow you to play with texture.