There are always mysteries in old cookbooks, because even the most unpoetical depend on the existence of a living tradition for the cook to know when the result is correct.

-Charles Perry, from In Taste: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery

I think this post is particularly appropriate to the Christmas season, as in the next couple days thousands of cookbooks will be purchased and given as gifts, and even more recipes will be searched out online and acted out in home kitchens.

I think this post is particularly appropriate to the Christmas season, as in the next couple days thousands of cookbooks will be purchased and given as gifts, and even more recipes will be searched out online and acted out in home kitchens.

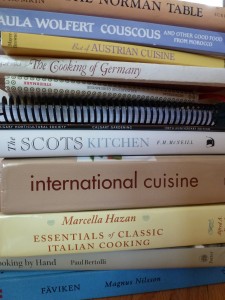

I myself already have an Alexandrian hoard of cookbooks. Some of them are completely useless. Others have changed the trajectory of my career and home-life. I also record recipes very meticulously, and oftentimes those recipes get published on this site. If you can’t be in the kitchen with someone then a recipe is as good a way as we have to teach them how to cook a certain dish.

That being said, recipes are not everything that we think. They are not the secret essence of the dish, and rote following of a recipe is no more effectual than reciting the words of a prayer. A recipe on its own, no matter how detailed, is woefully insufficient if the cook is not familiar with the dish and the traditions from which it comes.

Let me explain.

Part One: Technique-Driven Cooking

Give a man a fish, feed him for a day.

Teach a man to fish, feed him for life.

-Chinese proverb? As a child this saying was always attributed to “ancient Chinese wisdom,” but for all I know it’s from Reader’s Digest.

Once I had gained a bit of confidence in the kitchen, I eschewed recipes. This was partly because I had a basic idea of the proportions needed make mayonnaise, or beef stew, or mashed potatoes; it was partly because I thought I could adjust salt, vinegar, and spices by following my own palate; but mostly it was because I realized that technique affected the final dish far more than the amount of any one ingredient used.

By way of example, let’s discuss How to Cook Green Vegetables. Here is a description of how to blanch asparagus, taken from a recipe in Joel Robuchon’s The Complete Robuchon:

Wash and trim the asparagus. Prepare a dish lined with 4 layers of paper towels. Bring 2 quarts (2 l.) water seasoned with 1 tablespoon coarse salt to a boil in a large pot. Plunge the asparagus into the simmering water and cook for 2 minutes, turning them with a skimmer. Remove with a skimmer or slotted spoon to the paper towel-lined dish to dry, patting it with paper towels as necessary.

These are very specific instructions that will no doubt yield bright green, firm but tender asparagus (though 2 minutes seems like a long time for anything but the oldest stalks…) Now compare that passage to the following excerpt from The French Laundry Cookbook:

Raw green vegetables appear dull because a layer of gas develops between the skin and pigment. Heat releases this gas, and the pigment floods to the surface. But this happens fast, and pretty soon, as the vegetable cooks, the acids and enzymes in the vegetable are released, dulling the green color. At the same time, pigment begins to leach out into the water. So the challenge is to fully cook a vegetable before you lose the color, which means cooking it as fast as possible. There are three key factors to achieve this. First, blanch in a large quantity of water relative to the amount of vegetables you’re cooking, so you won’t significantly lower the boiling temperature when you add the cold vegetables. If you lose the boil, not only do the vegetables cook more slowly, but the water becomes a perfect environment for the pigment-dulling enzymes to go to work (these enzymes are destroyed only at the boiling point). Furthermore, using a lot of water means the pigment-dulling acids released by the vegetables will be more diluted.

Keller goes on the explain the importance of heavily salting the water, and of shocking the vegetables in ice water once they are cooked through. Keller’s description of big-pot blanching is more useful than one hundred recipes on blanching the several green vegetables available to modern cooks. More essential, transferable information is conveyed than any number of ingredient-lists and procedures. In other words, the Robuchon recipe gives you bright green asparagus every time you prepare that specific recipe, while Keller gives you bright, green vegetables for the rest of your cooking days!

For the sake of completeness, below is a picture comparing the colour of dull, raw peas (above) to vibrant, blanched peas (below).

Another case study: How to Brown Meat.

Here’a description of how to brown beef from The Complete Robuchon.

Heat the … olive oil in a large pot over high heat. When the oil is hot, add the stew meat and brown all over, about 5 minutes. Remove the meat to a dish with the skimmer.

This, I think you will agree, is another very precise but more or less useless instruction. What is hot oil, for instance? What shade of brown should the meat be?

The colour of properly browned meat and the methods to produce it are difficult to convey in a cook book. And there is no formula for telling how long it will take to cook a certain piece of meat to perfect doneness.[1] In fact, Brillat-Savarin went so far as to say, “We can learn to be cooks, but we must be born knowing how to roast.”

I didn’t learn how to brown meat until I worked at Jack’s Grill. Most of the proteins were seared in aluminum frying pans. We would put a bit of grapeseed oil in the pan, then put it over medium high heat. Only once the oil was starting to smoke did we add the meat. This is the heat that is required to properly brown a small piece of meat without over-cooking the interior.

I would describe the colour of well-seared meat as deep amber. Bits of fat should be a lustrous bronze.

The best technique-driven books I’ve come across are Ruhlman’s Twenty, and On Food and Cooking (perhaps a bit dry and scientific for the beginner, but it has several important details about technique). There are several brilliant books from famous chefs and restaurants that are structured as cookbooks (ie. a set of recipes), but are much, much more valuable for their spirited insights into techniques. Fergus Henderson’s The Whole Beast comes to mind, as the recipes themselves are too cursory to be truly useful, but the broader ideas on how to prepare off-cuts are brilliant. Curing, breading, and deep-frying a pig’s tail, for instance. I feel similarly about Magnus Nilson’s Faviken and The Art of Living According to Joe Beef. Fantastic books, but not because of the recipes themselves.

Part Two: Ratio-Driven Cooking

The first person to really open my eyes to the power of ratios in cooking was Michael Smith. In the cheesey introduction to his Food Network show Chef at Home, he says, “My secret recipe? Cooking without a recipe!” Corniness notwithstanding, I think Michael Smith did a great job of teaching essentials about ingredients, flavours, technique, and ratios. I remember him making a barbecue sauce using equal parts ketchup, brown sugar, mustard, and vinegar. This is far from the perfect barbecue sauce, but it’s a fantastic starting point that frees you from recipes. It’s easy to remember. Mix the ingredients, then have a taste. More acid? More sweetness? Add onions or garlic or paprika or cayenne? This is the kind of starting point someone needs to develop their own repertoire.

A few years after this introduction I read a book called Ratio by Michael Ruhlman. Ruhlman is one of the most influential food writers in the States (he had a hand in The French Laundry Cookbook, and helped fuel the charcuterie renaissance with his book Charcuterie). Of the five books that most changed how I cook and think about food, three of them are at least partly written by Ruhlman, and Ratio might be in first place.

Case Study: Crêpes

Ruhlman explains that the basic ratio to make crêpes is 2 : 2 : 1, liquid : egg : flour. This is dead-simple to remember. The most common form would use milk and all-purpose flour. Change a third of the flour content to ground wild rice, and fold some cooked wild rice into the final batter and you’ve made wild rice crêpes without a recipe.

The book contains ratios for everything from baked goods to sausages to custards.

Conclusion: The “Food” Section at Chapters

The mother of excess is not joy but joylessness.

-Nietzsche

Based on observations during periodic visits, I think “Food and Cooking” is the fastest growing section in the bookstore, besides possibly “Graphic Novels.” It is a seductive set of shelves, with heavy folios and gorgeous photography.

But.

Have you ever walked through a dollar store and felt a little bit sick in thinking about all the cheap plastic junk in the world that doesn’t need to exist? Lately I’ve felt that way about cookbooks. There are many fantastic books on those shelves – a few of them have quite literally changed my life – but most of them are unnecessary, redundant cash grabs.

I see the proliferation of cookbooks as a symptom of the meager culinary traditions in our society. Frankly the proliferation of foodblogs is the same. While there are some very, very useful books out there, what folks interested in cooking need to do is find a friend, relative, or business that can show them how to cook. There are countless ways to do this in Edmonton. Small cooking schools and conferences are popping up all over (eg. Get Cooking, Taste Tripping, Seasoned Solutions, Allium Foodworks, Eat Alberta.) Shovel and Fork is a lot broader than “cooking,” and offers classes on several food crafts like gardening, cider-making, and pickling.

Last year I helped Kevin Kossowan host a hands-on pig-cutting day at Sangudo. After some preliminary explanations and words of advice, it was time for the students to pick up their knives and cut up the pigs. “How should we hold the knife? Like we’re cutting a steak? Where should we cut? Where exactly?” After a few such questions I had to stop answering, and only reply, “Just start doing it,” again and again, until they did. With that single stroke of the knife, each nascent meat-cutter immediately learned something that no book could ever teach them. Then they were off to the races and the learning and the conversation could really begin.

1. The folks at Rational probably disagree with this statement.