While the most famous incarnation of this cut of pork is bacon, fresh pork belly has become very popular over the last few years. In the butcher shop it is also called pork side, or side meat. Before I started buying pigs by the side, I ordered slabs of belly from Irvings Farm Fresh, a 5 lb slab costing somewhere around $25.

A Quick Tour of the Pork Belly

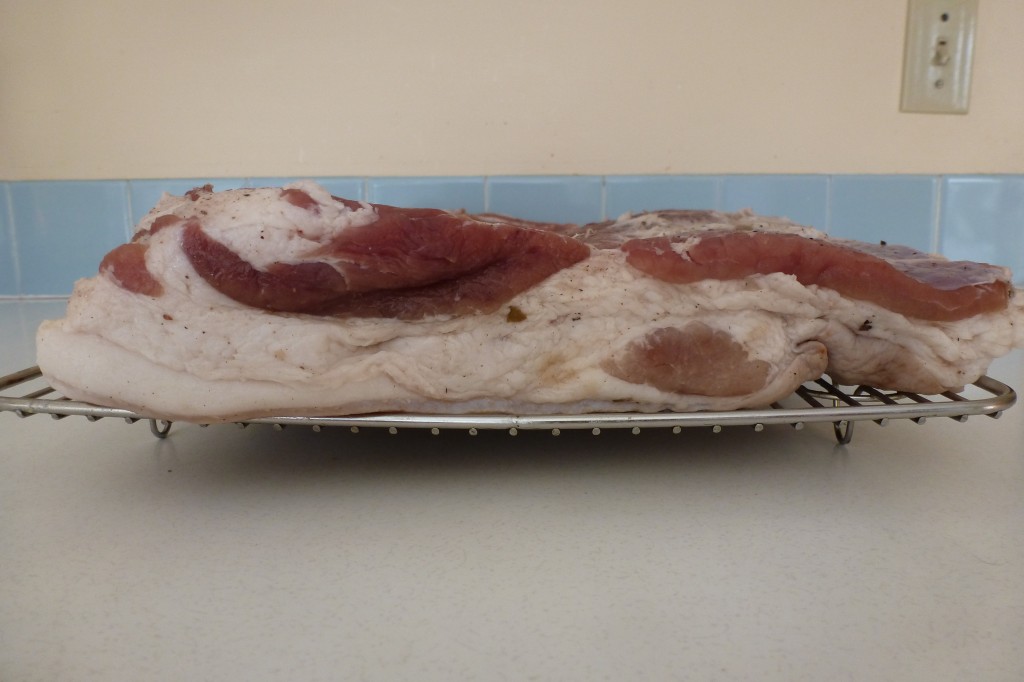

Below is a slab of pork belly. You’re looking at the inside of the pig; the opposite side is covered with skin. The right side of this slab would have connected to the front shoulder of the hog. The left side would have connected to the hind leg. The top was once connected to the loin, and the bottom to another belly slab at the sternum of the pig. Do you see the diagonal line that runs roughly from the top left to the bottom right? That would be the perimeter of the rib cage. The section to the top right once clung to the pig’s ribs, and you can actually see the pattern of the ribs in the vertical lines of meat and fat. The lower left section of the slab was outside the rib cage. The boundary between those two sections is the diaphragm, though most of the actual diaphragm muscle has been trimmed off.

Since we’re discussing anatomy, I might as well point out that the different parts of the belly have different eating and cooking qualities.

Here is a picture of the right end of the above belly slab, that is, the side once attached to the front shoulder of the pig.

Here is the left side of the belly, which connected to the leg. You can see that it doesn’t have nice, alternating layers of meat and fat, but rather a few isolated muscles separated by a large amount of fat. I find this “leg end” a bit fatty to be cooked and eaten as is. I might consider curing this part, then chopping it up and frying it to render out the fat, then cook Brussels sprouts or beans in the same pan. It would also be most welcome in a sausage mix. Also be aware of glands: there are several where the belly meats the leg, near the groin.

Finally is a cross-section from the middle of the belly. Here we have meat and fat in almost equal proportions, and in the nice, alternating, streaky pattern we expect from pork belly.

Cooking Pork Belly

Pork belly is roughly equal parts meat and fat, though obviously the exact ratio will depend on how the pig was raised. The high fat content means that belly should be cooked low and slow to render properly. The meat itself is made of fairly tough muscles, another reason belly requires lengthy cooking. It can be braised or slow-roasted. I prefer slow-roasting, unless I absolutely need to make a sauce, in which case braising is useful.

You can brine pork belly for a bit more moisture, but there is enough fat that I don’t think this is necessary. The cut does benefit from judicious salting well before you intend to cook it (say, 6 hours earlier) so that it’s seasoned throughout.

To slow roast I season early, then cook the belly in a 250°F oven for a few hours.

Because the belly is a flat, rectangular prism, it is often cut into tidy little cubes or prisms. The irregular leg-end tends to bunch up when cooked, but if you weigh the belly down for an hour or two after cooking it will flatten out again.

The flat shape also means that it can be rolled into a cylinder. Say, filled with herbage for a modern porchetta.

Like bacon, fresh belly can benefit from a secondary cook to crisp and render further, those this isn’t strictly necessary.