Even though maple syrup is popularly described as a “Canadian” ingredient, I consider it a highly regional specialty within Canada, as it’s only made on a large scale in Eastern Ontario and Quebec. In contrast to the sugar maples that grow down east, the maple trees around Edmonton produce less, and less sweet, sap. Birch and elm can also be tapped for sap, but they have even lower yields.

These facts notwithstanding, I have a perverse obsession with maple syrup (one of my favourite desserts of all time is pouding chômeur) as well as an abstract, academic nostalgia for the ingredient. Granulated sugar is one of the few highly refined products that I use regularly, and I’m interested in finding ways to replace it with, say, honey and maple syrup. Consider this:

For the colonists, maple sugar was cheaper and more available than the heavily taxed cane sugar from the West Indies. Even after the Revolution, many Americans found a moral reason for preferring maple sugar to cane; cane sugar was produced largely with slave labor. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, cane and beet sugar became so cheap that the demand for maple sugar declined steeply.[1]

Besides all this, making maple syrup has an extremely low effort-to-benefit ratio: by drilling a hole in a tree and boiling the sap that leaks out, you can enjoy one of the great pleasures of the table.

In the spring of 2011, Lisa and I moved to a new house. The backyard of that new house was a bit like a wrapped birthday present. The wrapping was the three feet snow concealing the features of the yard. There were small tears in the wrapping, if you will: the tops of wooden stakes, promising some manner of garden; shrunken, frozen apples on one of the trees; and best of all, clinging to the topmost branches of a tall tree, those winged seed pods that fall to the ground spinning like propellers. Maple keys.

I resolved to tap this maple tree, even if it was of the low-sugar variety. I had only the most basic idea of how to do this.

Part One: Tapping

Some guidelines:

- Any maple with a trunk wider than 10″ in diameter can be tapped without damage to the tree.

- Tap the tree when the sap is running. The sap runs during the spring thaw, when the days are warm and nights are cold.

- To tap the tree, drill a hole that is slightly smaller than the diameter of your spile (the metal spigot). The hole should go 2-3″ into the trunk, at a 10-20 degree incline, anywhere 2-6′ from the ground. Apparently south-facing holes have a higher yield in the earlier weeks of the sap run.

- Lightly tap the spile into the hole and hang a bucket to collect the sap.

Some day in the future I may buy proper spiles and buckets. In the meantime I used some 1/2″ copper pipe from the plumbing section of the hardware store, and a plastic bucket supported by a wall hook. I covered the bucket with a plastic bag so that nothing could fall into the sap.

The first tree I tapped actually forks into two large trunks. Since both trunks are more than ten inches across, I put one tap in each. Part way through the sap run, I realized that I have another maple tree on the other side of my yard, so in total I made three taps.

Here is the forked tree, on the east side of my backyard.

And here is the tree I missed at first, tucked away in the soggy southwest corner of the yard.

Part Two: Collecting

Some time on or around Saturday, April 2, 2011, the sap in my first maple tree started running.

Some observations:

- the sap runs during the day, not so much at night

- the sap looks pretty much like water

- the specific gravity of the sap is 1.008 (small but detectable amounts of sugar)

- the sap tastes every so slightly sweet, with some very pronounced flavours: woody, nutty, very “green”

- I think I could drink a glass of the sap with breakfast every morning for the rest of my life

The buckets have to be emptied every day. Some days they would have overflowed if they hadn’t been emptied. Even during periods of low flow, it’s best to empty every day to maintain the freshness and cleanliness of the sap.

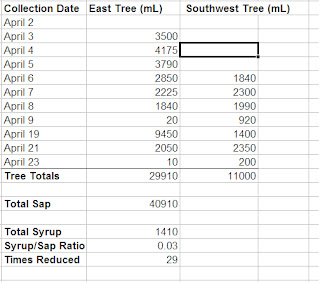

Sap flow started very high, then tapered quickly (daily sap quantities are listed below). The first full day of the run I got about 4 L from the eastern tree.

Part Three: Boiling

As I mentioned above, the sap itself is delicious, even without being reduced to syrup. If you are only tapping one tree, you might get more bang for your buck by drinking a few litres of sap instead of reducing to get a cup or so of syrup. Something to consider.

Either way, strain the sap to remove any debris and store in the fridge.

Once you’ve collected enough sap to fill a stock pot (10 L in my case), boil the sap over medium high heat. I was cautioned to do this outside, as allegedly a sticky residue can build up on surfaces if done indoors. I ignored this caution and boiled the sap on my stove with the vent hood running. No residue appeared, perhaps because I was processing a relatively small amount of sap.

As soon as the sap is brought to a simmer, it turns from clear to cloudy. If you continue to boil the sap down you get a very murky syrup that looks a lot like honey:

If you want clear syrup, you have to remove the “sugar sand,” the calcium compound that is clouding the liquid. Lisa and I simply stopped boiling partway through the reduction, let the sugar sand settle to the bottom of the pot, then decanted the syrup and continued boiling. My understanding is that the sugar sand is not harmful in any way; it’s removed simply to clarify the syrup. Here’s a picture of some of the sugar sand we filtered out:

If you’re diligent with your decanting and filtering, you will end with a more familiar looking, clear syrup.

I didn’t reduce my syrup to the same thickness as commercial syrup. Besides being less sweet, the flavour of my syrup is much different than store-bought: there is a pronounced fruitiness, one that I would associate with a fine honey.

Part Four: Analysis

Below are the quantities of sap I collected each day. Note how the flow starts very high, then tapers to almost nothing in a matter of days. At this point I thought that the run had ended, and I stopped checking my buckets. Then about a week later I was in my backyard and noticed that the buckets were overflowing. Some of the sap was lost, but I don’t know exactly how much. Also, I don’t know if the break in the flow had to do with the weather (it was very cold and overcast on those days), or if it is part of a regular cycle in the run. Interestingly, the second wave of the run produced noticeably sweeter sap.

The maple syrup article in On Food and Cooking says that sugar maple sap is typically reduced by about 40 times, and birch sap by about 100 times. Having a maple tree, but not a sugar maple, I was expecting to reduce somewhere between 40 and 100 times. I ended up reducing by only 29, though, as I mentioned above, my final product was not as thick and sweet as commercial syrup.

Tapping the trees took about ten minutes. Emptying and straining the sap took about ten minutes each day of the run. Boiling the sap down took a few hours every few days of the run, but obviously you don’t have to stand over the pot and watch the liquid reduce. In the end I got a litre and a half of syrup, which I suspect will amply garnish our pancakes for a year.

For the longest time I thought that there are few maples around Edmonton, and that the ones that are here are no good for syrup. I was wrong. Now as I walk through my back alley in McKernan, I see suckering maples everywhere. Most of them are too small to tap, but there is still a huge amount of “untapped’ sweetness in our city. Maples, like caragana, are much more common in the older communities of Edmonton than in the newer suburbs, as they are considered “messy” plants, what with all the suckering and keys…

Tapping maples in Edmonton is not only possible, it is worthwhile, and you should try it if you have the opportunity. Next winter I’ll put a small ad in my community newspaper to see if there’s anyone interested in learning to do this. If you have a mature maple (or birch) tree in your yard, here are some resources for you.

- A great website with lots of detailed information: http://www.tapmytrees.com/

- Mack, Norman (ed.) Back to Basics: How to Learn and Enjoy Our Traditional Skills. ©1981. The Reader’s Digest Association (Canada) Ltd. Montreal, QB.

- Or contact me through Button Soup

Reference

1. McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking. ©2004 Scribner, New York. Page 668. I love this book.

Now tell everyone the ratio from sap to syrup…! Shocking!

Uncle Howard would be so proud of you!!

Remember how I said it tasted like it must be super healthy for you? It's a fact, as per this article about people in South Korea drinking it:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/06/world/asia/06maple.html

Forget the syrup, we should just drink it.

Thanks for posting this. I picked up two maple tapping thingys when I was in Montreal last year and am really looking forwrad to trying them out. any good suggestions where to go here in Edmonton? I would of course ask the home owner. unfortuneately I have no trees of my own.

Thanks

Rob Thomas

Hi Rob. My observations suggest that communities developed in the 1960s or earlier have plenty of Manitoba maples. So far, though, it hasn’t been a good year for the sap run. We went from below-zero days and nights, straight through to above-zero days and nights, with no period of diurnal fluctuation around the freezing point. That may change, though.