On March 1, 2017 I’m teaching a class for Metro Continuing Education called Deep-Frying Without a Deep-Fryer. Course details are available here. I thought I’d re-post this old article, a vehement defense of this most venerable technique. Originally published March 23, 2014.

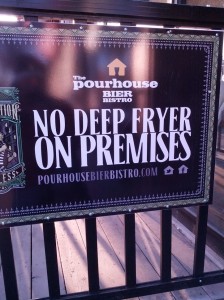

Yesterday I was walking on Whyte Avenue and I saw a sign that upset me. It was outside The Pourhouse, a tavern with a clever name and a broad selection of beer and food. The poster read “No Deep Fryer on Premises.”

Yesterday I was walking on Whyte Avenue and I saw a sign that upset me. It was outside The Pourhouse, a tavern with a clever name and a broad selection of beer and food. The poster read “No Deep Fryer on Premises.”

I perfectly understand the intentions of this advertisement. I have been to bars where the food is clearly manufactured off-site, purchased frozen, plopped into a deep fryer, and garnished with green onions or bottled plum sauce or nothing. If you don’t quite understand what I’m talking about, go to Rosie’s at 11 pm and order something. Bathe in the neon lights and try to enjoy the plate of perogies or spring rolls or green onion cakes or whatever you ordered. Then you will know the horrors of which I speak. Anyways. The implication of the Pourhouse ad is that they prepare thoughtful, fresh, delicious food. I get it.

In fact, I have more reason than most to hate deep-frying. Early in my cooking career I worked at Dadeo, the Whyte Avenue Cajun diner. It was an oddly segregated kitchen: there was a prep team of kindly Chinese-Vietnamese ladies, and a line-team of white kids. The first station for new line-cooks to learn was the deep fryer, and you would be hard-pressed to find a restaurant in Edmonton that puts more food through a deep fryer than Dadeo. The fryer itself is roughly the size of a bath tub, partitioned into three compartments. Approximately half the menu goes through this machine: of course there are the famous sweet potato fries, but also the several breaded seafood items for the po’ boys and jambalaya plates, as well as fritters, spring rolls (“Cajun cigars…”), fried chicken, calamari, breaded eggplant, and crabcakes. Oh, and Sunday nights are wing nights. Even though that deep fryer holds about 50 L of canola oil, it is usually the bottleneck that ever-so-slightly slows the break-neck service at Dadeo. Anyways. I spent a couple months working the fryer at Dadeo. The inexpungeable stench of dirty oil in my clothes and the second degree burns on my hands notwithstanding, I still love fried food.

The Pourhouse sign is not the first time I’ve encountered the pretentious scorn of culinary types who look down their noses at deep-frying. Hatred of fried food confuses me a great deal, as I’ve always considered it a delicacy. Not many folks fry at home anymore, I think because of the misconception that you need a “deep-fryer” to deep fry food. Really you need a stove, a pot, and a jug of oil. A thermometer is also useful, but by no means necessary.

Fried food is outdoor food. Finger food. Carnival food. Seriously: what is more magical than going to a fair and seeing those little rivers of hot oil carrying mini doughnuts to their sugary terminus? In Europe many fried treats are associated with the revelry preceding Lent. The Krapfen of Austrian and Bavaria, for instance, or the fritoles of Venice. Street food. Festive food.

Fried food is the singular joy of eating out with friends and family. Every single time I ate French fries before the age of sixteen, I was at a restaurant with friends and family. I never once ate them at home.

Fried food is comfort food. What is more satisfying after a walk in the winter cold than a big, breaded, fried schnitzel? (Every Austrian I’ve ever met has acknowledged that schnitzel is traditionally pan-fried, “swimming” in oil, but then, a few minutes later, they all concede that modern schnitzel is best deep-fried.)

If you still aren’t convinced that deep-frying deserves your respect, you should read the section of Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology of Taste called Theory of Frying. No clearer, more succinct, playful description of a cooking technique has ever been written. Especially charming is his description of the “surprise”: the moment the food is dunked in the oil, and the immediate, vigorous bubbling that takes place after.

So you can see that I have several pleasant associations with deep-frying. So much so that before I got angry with the Pourhouse sign, I got a little sad. No deep fryer? Oh. So you don’t have French fries? At a bar? So no fish and chips? And no poutine? Oh: you do have poutine, but it’s made with roasted potatoes? (Poutine made with roasted potatoes is where I transitioned from sad to angry.)

Below are apple fritters that I made last fall. Apples grown within the Edmonton city limits, peeled, cored, and sliced into rings. I made a yeasted batter with eggs, flour, sugar, and a bit of cider from last season. The apple rounds where dredged, fried, dusted with icing sugar, and served with heavy cream. I consumed the fritters outdoors, during the intermission between rounds of pressing cider.

I hope that this example demonstrates that deep-fried food can be thoughtful. When made with care, deep-fried snacks are some of the most profoundly satisfying foods we have.

More on Fried Food: